A New Way to Tell Molecular Isomers Apart

Most people never think about how molecules move. Even many chemists, according to Dr. Liam Michael Duffy, don’t realize that gas molecules are not free to tumble however they please. “As small as they are, they must obey the laws of quantum mechanics,” he explains. Their rotational motion is constrained to discrete, fixed amounts of energy, dictated precisely by their mass and shape. When electric fields are applied, those same molecules can only orient themselves at specific angles— “like microscopic precessing gyroscopes”—a phenomenon known as the Stark Effect.

For Duffy, a physical chemist at UNC Greensboro, this hidden order has long been a source of fascination. But it wasn’t until a pivotal research collaboration overseas that he began to see how these quantum rules might solve a much more practical problem.

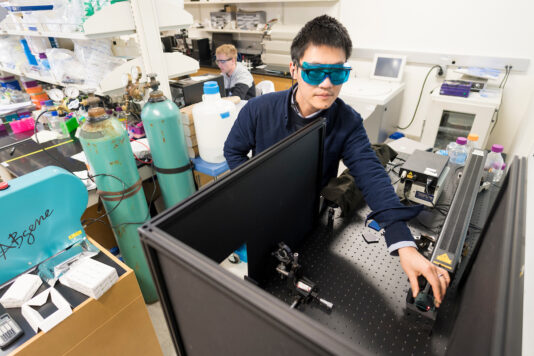

About fifteen years ago, Duffy was invited to work with researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin, where scientists were conducting ultra-cold chemical physics experiments. Inside vacuum chambers, streams of gas molecules were slowed, stopped, and trapped at temperatures just fractions of a degree above absolute zero—conditions where molecules behave more like waves than particles. These experiments relied on massive, multimillion-dollar machines stretching meters in length. But during Duffy’s visit, the Berlin team had begun shrinking that complexity into chip-sized devices, no larger than a microscope slide.

“I was there to do interesting things to the molecules with microwave technology that I brought with me from my lab at UNCG,” Duffy recalls. “But I left Berlin wanting to design and build my own chip-like molecule decelerator.”

The challenge was that the simplified device worked well for only one molecular species: carbon monoxide. For nearly a decade, Duffy and his students tried—and often failed—to design something that could work on generic molecules. Progress came unexpectedly, sparked by an earlier paper from the same Berlin group that described a large quadrupole device capable of separating molecular conformers—molecules made of the same atoms but twisted or puckered into different shapes.

That insight changed everything. Duffy realized that the same approach could be used to distinguish molecular isomers—molecules that share identical atomic compositions but differ in structure. “Just like anagrams,” he explains, “you can rearrange the same letters to make entirely different words.” In chemistry, those differences can be profound: one arrangement might become a life-saving drug, another a toxic compound, and another a useful consumer product.

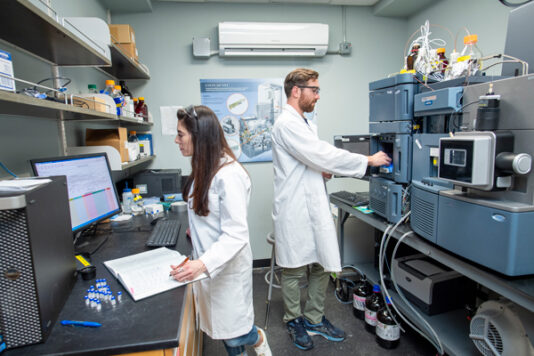

Yet identifying isomers remains one of the most stubborn problems in analytical chemistry. Mass spectrometry, a cornerstone tool, can determine how heavy a molecule is, which often reveals which atoms are present. But mass alone cannot show how those atoms are arranged. Because isomers weigh exactly the same, chemists are forced to rely on indirect clues, like fragmentation patterns, or time-consuming pre-separation techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography. Even then, results can be inconclusive.

“The central job of any analytical chemist is to identify what molecules are in a sample,” Duffy says. “And this is one of the places where existing workflows can break down.”

Duffy’s solution is a new kind of instrument: a Mass Starkometer. Instead of ionizing molecules, as traditional mass spectrometers do, the Starkometer works with uncharged, polar molecules. By exploiting the Stark Effect, high electric fields guide these molecules through microscopic electrode structures, subtly pushing or pulling them based on their shape and polarity. In principle, isomers that look identical to other instruments can be separated and identified directly, without extensive method development.

Turning that principle into a real device has been anything but straightforward. “As far as we know, this is the first attempt to make a microscopic device that guides polar gas molecules between microfabricated electrode structures,” Duffy notes. Simulations suggest the concept works, but building hardware introduces countless unknowns—materials, alignment, electronics, sensitivity, and the simple reality that equipment can fail. Instrument development, unlike software, requires patience and iteration, often discouraging early private investment.

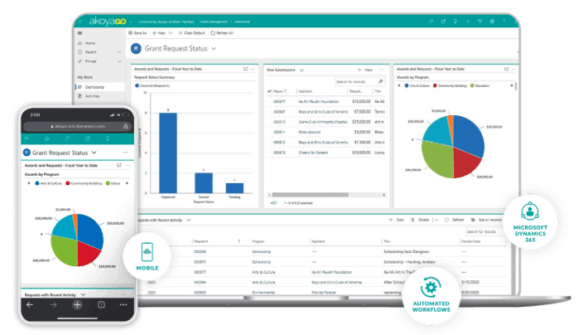

Before receiving NCInnovation support, Duffy’s spinout company, Moires Instruments Inc., relied on a Phase I NSF Small Business Innovation Research grant and a state matching award. While critical, those funds came with limitations—most notably, restrictions on purchasing essential equipment. At one point, a failed electron gun stalled progress for six months. “For an instrument development project, that was quite limiting,” he says.

NCInnovation funding removed those barriers. With the flexibility to acquire high-end equipment, Duffy and his team are now working toward clear milestones: realistic simulations matched to experiments, guiding polar molecules through the device, demonstrating isomer separation, and adapting the system for continuous flow so it can integrate with existing tools like gas chromatography.

The implications could span industries—from pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals to consumer chemicals—where regulatory approval hinges on identifying and quantifying isomeric metabolites. Through customer discovery, including insights gained during an I-Corps interview with Syngenta, Duffy learned how deeply these bottlenecks affect development timelines and costs.

For Duffy, success is not just technical. It is about creating a new platform for the chemical and life sciences—one that could become a standard tool in analytical labs. At the same time, he envisions a North Carolina–based company capable of offering services or instrumentation, while he continues advancing the underlying science at UNCG.

“My understanding is that merely having a good idea, patented or not, is not enough,” he says. “It often takes a small startup to de-risk the technology before others will adopt it.”

By helping bridge that gap—from quantum physics to practical instrumentation—NCInnovation is enabling research that reveals differences most tools cannot see, and in doing so, may change how molecules are understood, identified, and ultimately used in the real world.