An Engineer’s Approach to Restoring the Body’s Natural Repair Process

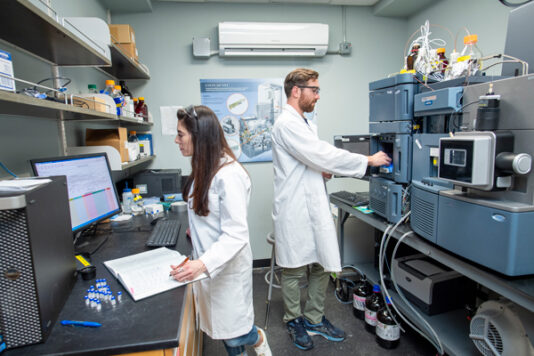

For more than fifteen years, Amay J. Bandodkar, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at North Carolina State University, has been drawn to the question of how technology can improve human health. As an undergraduate researcher, he began working on biomedical devices and biosensors—tools designed to measure, monitor, and diagnose. Over time, that work matured into deep expertise in personalized diagnostics. But for Bandodkar, diagnostics were never the end of the story.

“While working in this field is very satisfying,” he explains, “diagnostics is only one key piece of healthcare, with treatment being the other.” Increasingly, he began asking whether the same engineering principles he had applied to sensing and measurement could be leveraged to actively help the body heal. That question ultimately led him to wound care—an area where the need is immense, the stakes are high, and existing solutions often fall short.

Chronic wounds, particularly diabetic foot ulcers, represent one of the most persistent and devastating challenges in modern medicine. Diabetes is a systemic condition that affects blood flow throughout the body, and over time can lead to peripheral arterial disease. Even when blood glucose levels are later well controlled, impaired circulation can severely inhibit the body’s ability to heal. As Bandodkar notes, it is estimated that 1–2% of the global population will experience a chronic wound during their lifetime. For patients with diabetic foot ulcers, the consequences are especially dire: they are ten times more likely to undergo amputation, face mortality rates three times higher than those without ulcers, and incur treatment costs that are 50–200% greater than baseline diabetes-related care.

Behind those statistics are day-to-day realities that are often invisible. “On a day-to-day basis,” Bandodkar says, “the quality-of-life decreases; financial burden increases; mobility and socialization is reduced.” Patients may experience pain or odor, require frequent clinic visits or home nursing care, and face repeated hospitalizations. Over time, many lose their independence entirely.

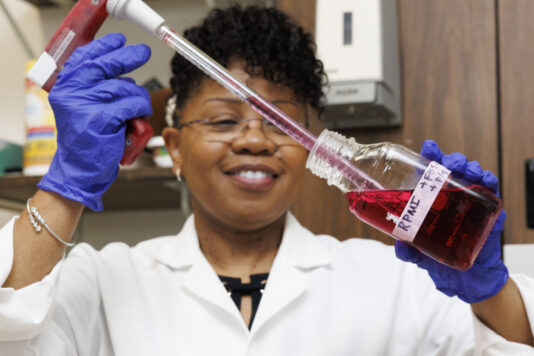

For an engineer with a background in wearable technologies, wound care presented both a challenge and an opportunity. “As an engineer, I find working in this space very interesting because it involves unique challenges that require innovative solutions that cut across diverse fields in engineering and medicine,” he says. His interest deepened while working on a DARPA-funded project focused on wound care systems designed specifically for resource-limited settings—environments where cost, training requirements, and infrastructure constraints often make advanced treatments inaccessible.

One of the most significant barriers Bandodkar observed was the limitation of existing FDA-approved wound therapies. Many are expensive, offer relatively low efficacy, and require trained personnel to administer. “These factors collectively make present wound treatments inaccessible to many individuals,” he explains, particularly those in remote locations or facing financial constraints. His goal became clear: to develop a wound care technology that was not only effective, but also affordable, easy to use, and scalable.

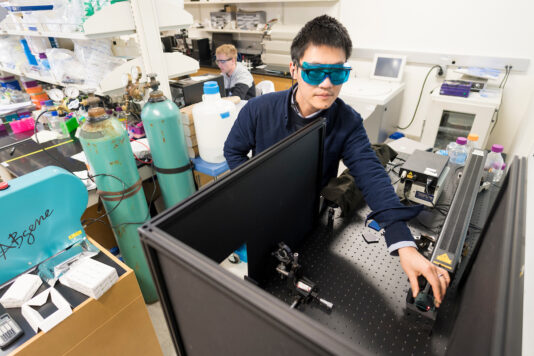

The result is an electric bandage that works by supporting a process the body already uses to heal itself. Human cells communicate through the movement of charged ions. When a wound forms in a healthy individual, the normal flow of these ions is disrupted, creating an electric field that directs cells toward the center of the wound, helping it close. In chronic wounds, however, these electric fields are significantly weakened, slowing or halting healing altogether. “Our bandage boosts this weakened electric field,” Bandodkar explains, “and jump starts the healing process.”

Embedded within the bandage is a small battery that creates a controlled electric field when applied. The difference in potential energy between the battery’s anode and cathode generates the therapeutic signal—without causing any sensation for the patient. “They’re often curious to know if the bandage will make them feel a zing,” he says. “It will not.”

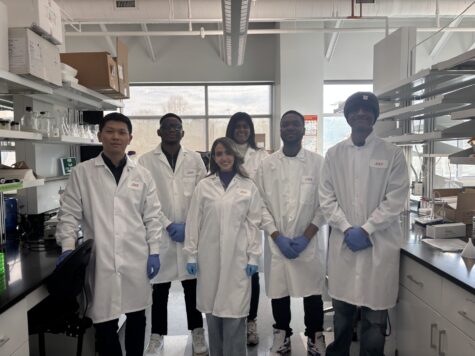

Animal studies conducted by Bandodkar’s team helped refine the design, optimizing electrode dimensions, battery size, and overall device architecture to ensure the bandage could be used by ambulatory patients. Just as importantly, manufacturability was considered from the very beginning. By using printing and die-cutting—two highly scalable, low-cost manufacturing processes—and pairing them with high-performance materials, the team designed a product intended for real-world deployment, not just laboratory success.

The bandage can be applied like any standard wound dressing, requires no specialized training, and delivers continuous therapy for at least five days. It performs reliably across a wide range of environmental conditions, from extreme cold to intense heat, and can be produced quickly and in large quantities—features that make it particularly well suited for home care, clinics, military environments, and disaster response settings.

NCInnovation funding plays a critical role in moving this technology forward. Bandodkar describes the support as essential during the “valley-of-death” phase, when many promising academic innovations fail due to lack of resources. With NCInnovation’s backing, his team aims to complete preclinical studies, develop a robust manufacturing strategy, identify the most appropriate FDA pathway for clinical studies, form a company, and secure additional funding to advance the work.

Equally important is listening. As part of the project, the team will conduct extensive interviews with clinicians, nurses, and patients to ensure the technology aligns with real-world needs and workflows. They are also exploring pathways for widespread adoption, including direct-to-consumer models and reimbursement-based access.

Success, for Bandodkar, is not defined by technical benchmarks alone. “Success to us would be that our bandages help patients in their wound recovery journey, reduce financial burden, and improve quality of life,” he says. Looking ahead, his hope is that electric bandage technology can help reshape the standard of care—making advanced wound treatment accessible to patients who today go without it due to cost, geography, or lack of trained personnel.