A New Way to Fight Mosquito-Borne Disease—Built in Western North Carolina

When a western North Carolina father rushed his young son to the emergency room for the third time in a month, doctors still couldn’t explain the seizures, vomiting, and confusion. The symptoms looked viral—but something was different. After repeated tests, the truth emerged: La Crosse virus, a mosquito-borne disease that primarily infects children and can leave lasting neurological damage.

La Crosse virus is often the most common mosquito-borne illness in North Carolina. It belongs to the same group of threats as dengue, West Nile, and Zika—diseases that continue to spread as weather patterns shift and mosquito populations grow. Yet for decades, local health departments have had to rely on slow, labor-intensive surveillance methods that require specialized technicians and waiting. When every day matters, that delay can mean the difference between early action and preventable harm.

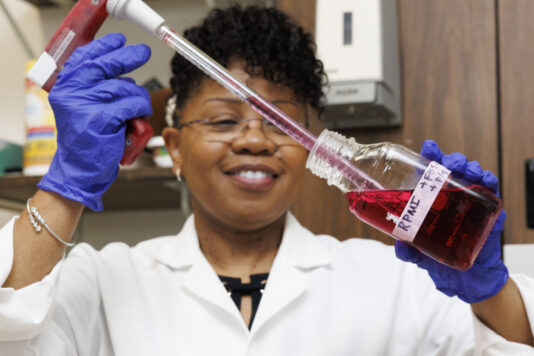

At Western Carolina University, Dr. Brian Byrd and Dr. Scott Huffman saw an opportunity to flip that model. Byrd, a medical entomologist with more than 20 years of experience, remembers the moment a colleague sparked a breakthrough.

“One of my colleagues saw us dissecting mosquitoes under a microscope and said, ‘I bet we can use spectroscopy to tell if those mosquitoes have laid eggs or not,’” Byrd recalled. “That’s how this whole idea started.”

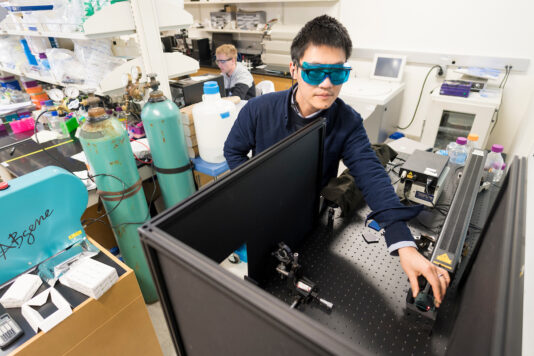

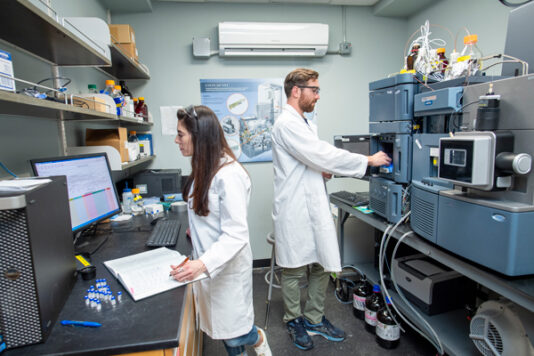

Spectroscopy—light-based technology that probes the composition of mosquitoes —had never been used this way. But Byrd and Huffman, a spectroscopy expert, began exploring whether those molecular fingerprints could reveal the traits that matter most to public health: species, age, reproductive status, and infection.

Using advanced mathematical models to separate and interpret spectral signals, they discovered they could analyze individual mosquitoes in minutes—without dissection, without fully destroying the sample, and without sending specimens across the state for testing.

With NCInnovation’s support, Byrd and Huffman are now advancing their proof-of-concept into a tool designed for real-world deployment: a low-cost, benchtop approach that could sit inside any local or regional health department.

“The big goal here,” Byrd explained, “is to create a tool that literally sits on a desktop at a local health department—something affordable, fast, and simple enough for everyday use.”

In under two minutes, their system can determine a mosquito’s species, age, and infection status—capabilities far beyond current surveillance tools. Instead of capturing and pooling 50 mosquitoes at a time and waiting days for lab results, local teams could scan individual specimens immediately and take action the same day.

The impact goes far beyond speed. Today, many counties spray pesticides preemptively because they lack timely data. Byrd believes this technology could change that.

“Our approach allows for targeted, data-driven decisions—fewer chemicals, less environmental impact, and healthier communities,” he said.

Huffman sees even broader potential. “This technology has global potential,” he said. “With NCInnovation’s business and commercialization expertise, we’re learning how to move from the lab to a viable, sustainable product. Their team is connecting us with regional innovation directors, helping us think strategically about markets and scaling.”

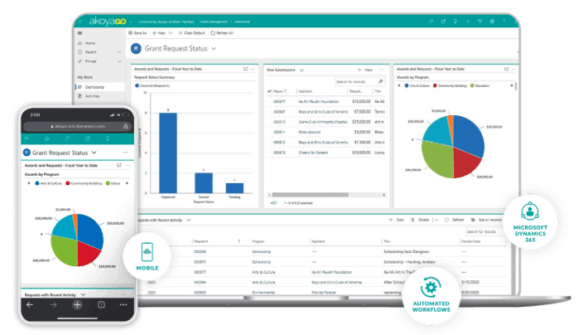

What started with La Crosse virus in western North Carolina is now expanding. The team is developing “data libraries” for dengue and West Nile, adding value for customers who could eventually purchase the device and subscribe to ongoing software updates. They envision a future where health departments—and even private mosquito-control firms—can map risks in real time.

In the long term, Byrd and Huffman imagine a dashboard that shows hot spots as they form, helping communities respond after hurricanes, floods, or sudden mosquito population spikes.

“Our technology can identify where mosquitoes are aging and when populations spike,” Byrd said. “That means we can predict outbreaks before they happen—and help prevent illness before anyone gets hurt.”

For Byrd, who began his career studying tropical diseases at Tulane, the work is deeply personal. It brings together science, community health, and a commitment to protect children like the young boy whose unexplained illness shook a family months before.

With NCInnovation’s support, he and Huffman are transforming mosquito surveillance from a slow, reactive process into a proactive safeguard—one that could change how communities across North Carolina, and eventually the world, respond to vector-borne disease.