Building a Biosecurity Platform to Safeguard North Carolina’s Agriculture and Supply Chains

The collaboration did not begin with a single grant or a single problem. It evolved over time, shaped by long-standing relationships and a shared interest in translating research into real-world protection.

“We’ve been working together for years,” said Roy Carter, Entrepreneur-in-Residence (EIR) on the project. “I first met TinChung when he was also a PI in The UNC System Research Opportunities Initiative (ROI) “game-changing” research, working in a different area. Even then, our work had potential for collaborations. We stayed connected, and when funding opportunities became available, we kept asking the same question: how can this research actually be used?”

That question —how can this be used –became the organizing principle of the project.

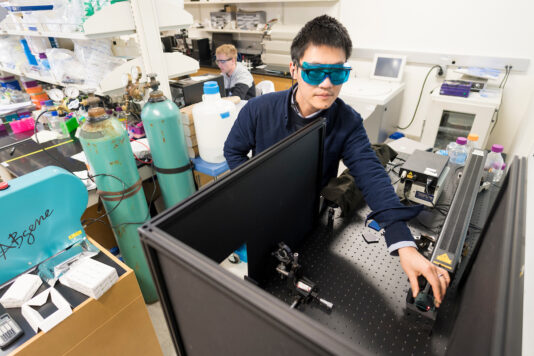

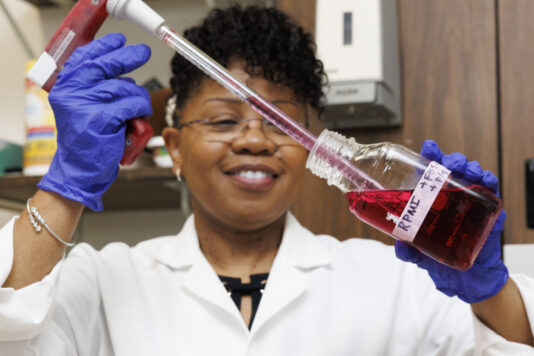

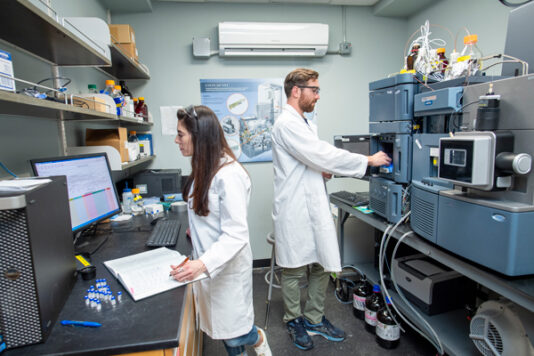

At North Carolina Central University, TinChung Leung, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Biological and Biomedical Sciences and the Julius L. Chambers Biomedical and Biotechnology Research Institute at North Carolina Central University (NCCU), had been working at the intersection of biology, genomics, and national security interests. His focus was not only on generating data, but on understanding how biological information could support real decision-making.

“My perspective always starts with the customer,” Leung said. “We look at the problem from the customer’s point of view and ask how genomics and data analytics can help them make better decisions. That means bringing different expertise together to solve a real problem, not working in isolation.”

Partnering with an industry partner on the project, the team set out to address the problem of biological risk– threats that could be intentional or accidental, known or unknown, and capable of moving across borders through trade, travel, and supply chains. This was made possible with Willy Valdivia, CEO of Orion Integrated Biosciences, who pioneered on advanced analytics, biosurveillance, and national security applications.

“We’re excited about this collaboration because it’s something different,” Valdivia said. “We began working with NCCU in a small way in 2020, and since then the work has attracted attention from multiple agencies. What’s unique is how we’re combining information– news, genomic data, and other signals– to support decision-making.”

At the center of the platform is a data-driven approach that connects events reported in the world with molecular-level information.

“Imagine there’s a news report about an Ebola outbreak in Africa,” Valdivia said. “On its own, that’s just information. But if we associate that event with genomic records, trade data, and transportation patterns, we can begin to assess whether there’s a pathway that could bring risk into the United States– and potentially into North Carolina.”

The system integrates more than 180 dimensions of data, spanning news sources, socioeconomic indicators, security data, and molecular biology.

“This is the paradigm,” Valdivia explained. “We’re marrying very different data dimensions– open-source information and genomic information– to support decision-making.”

For government agencies, the output is a risk assessment that translates complexity into something usable.

“A lot of this is about helping the U.S. government make decisions based on the best information available,” Carter said. “When you’re dealing with tens of millions of shipping containers entering the country every year, you can’t inspect everything. The system helps identify which situations represent higher risk and deserve attention.”

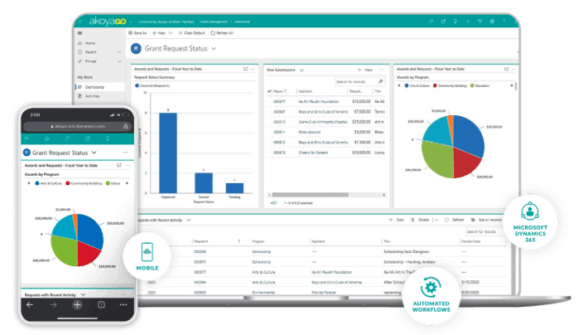

That assessment is operationalized through analytical dashboards that allow users to move from a high-level summary into detailed analysis.

“We can see what’s happening week by week, country by country,” said Anderson de Queiroz, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering (CCEE) at North Carolina State University, who contributes with data science, machine learning, and systems integration expertise to the project. “We look at reported cases, trade relationships, and commodities being imported. From there, users can filter for higher-risk scenarios and drill down into the details.”

The platform can even connect disease risk to specific commodities and shipping routes.

“If the data is available, we can identify the vessel, the port, and the type of commodity,” de Queiroz said. “That allows officers to focus inspections where the risk is highest.”

While national biosecurity is a central use case, the project’s impact extends into agriculture and ecosystems– an area where Gareth Powell, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Entomology at North Carolina State University, plays a critical role.

“There are many insects that look exactly the same,” Powell said. “Some are devastating pests. Others are harmless or even beneficial. Right now, we don’t have good tools to tell them apart in real time.”

That limitation has serious consequences for agriculture.

“In North Carolina, we’re an epicenter for certain turf and agricultural systems,” Powell explained. “Some beetles can cause billions of dollars in damage while others are part of the natural ecosystem. The problem is that the damaging stage is often the larva, which can be hard to find or identify when we do find it.”

Genomics offers a way forward.

“If we sequence the genomes, then it doesn’t matter what the insect looks like,” Powell said. “The genetics are the same whether it’s an adult or a larva. We can identify whether it’s a harmful species, a neutral one, or something we want to protect.”

Invasive species such as the Asian longhorn beetle illustrate the stakes. These pests can remain hidden in wood products or shipping materials and, once established, spread rapidly.

“When we get a pest like this, it doesn’t stay in one state,” Powell said. “It becomes everyone’s problem.”

The connection between national security, agriculture, and environmental protection is what makes the project distinctive– and what NCInnovation’s funding made possible.

“The NCInnovation grant is what allowed us to bring Gareth’s work into the project,” Carter said. “It enabled us to test agricultural and ecological use cases alongside national biosecurity. That convergence wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”

From the industry perspective, that convergence is essential.

“What’s unique here is that we’re not just collecting data or analyzing data,” Valdivia said. “We’re using it to build products and solutions. Most companies focus on open-source intelligence without genomics, or genomics without broader data context. This brings those worlds together.”

That includes the potential development of highly targeted biopesticides– countermeasures designed for specific threats rather than broad-spectrum chemicals.

“We can design very specific solutions much faster than traditional approaches,” Carter said. “That speed matters when you’re dealing with invasive species or emerging risks.”

Throughout the project, usability has remained a guiding principle.

“In the beginning, we had very complex visualizations,” Valdivia said. “But customers told us what they needed. They wanted something intuitive– green, yellow, red– something that fits into their operational systems and helps them act.”

For Leung, that focus reflects a broader shift in how academic research can function.

“The EIR role and the NCInnovation model helped us think commercially,” he said. “It pushed us to look at how a platform like this could serve different customers while keeping the science strong.”

In the end, the project is about preparedness and prevention.

“The cost of avoiding risk is small compared to the cost of responding after the fact,” Carter said. “Whether it’s a disease, a pest, or an unknown biological threat, having better information earlier changes everything.”